An unsigned review of Eliza Haywood's

The History of Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy appeared in

The Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science, and Art, vol. 20, no. 506 (8 July 1865): 52a–53b (

here). It seems to have been prompted by the writer reading Sir Walter Scott’s novel

Old Mortality (1816), which is alluded to at the start of this review.

In the Conclusion of

Old Mortality, an old woman declares: “I have not been more affected … by any novel, excepting the ‘Tale of Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy,’ which is indeed pathos itself.” The old woman is a figure of fun. In his autobiographical “Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott,” Scott writes: “The whole Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy tribe I abhorred; and it required the art of Burney, or the feeling of Mackenzie, to fix my attention upon a domestic tale.”

The old woman’s enthusiasm for the

History of Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy is not unlike Isabella’s enthusiasm for the “horrid novels” mentioned in

Northanger Abbey, books that had been so thoroughly forgotten that they “were later thought to be of Austen’s own invention” until “Montague Summers and Michael Sadleir re-discovered in the 1920s that the novels actually did exist.” (

here)

The anonymous author of the present review seems to have had a similar motivation to Summers and Sadleir: being an enthusiast for Scott (rather than Austen), and wanting to establish that

The History of Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy “actually did exist”—like the “Northanger ‘horrid’ novels.”

His conclusion is that

The History of Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy, not only exists, but "is skillfully constructed, without sacrifice of probability, or recourse to claptrap of any kind"—that it is "by no means a contemptible book … and if it never excites, it never becomes wholly devoid of interest."

Not only is this one of the longest, but it is also one of the fairest reviews Haywood's novel received in the two centuries following its release. It is a shame that [1] it is anonymous and [2] it has been overlooked completely. (For my post on "Eliza Haywood's Reputation before the 20C," see

here; for 18C reviews of works by Haywood, see

here.)

* * * * *

JEMMY AND JENNY JESSAMY.*

IN the preface or introduction to one of Sir Walter Scott’s novels, an old lady is represented discoursing with the author, and expressing her admiration of some previous production of his brain. The novel she commends is, in her opinion, the best that was ever written, except the

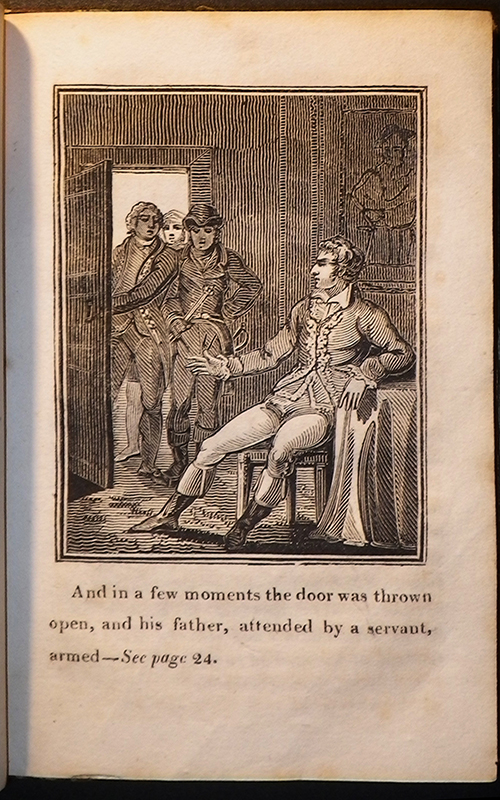

History of Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy. As for that immortal history, it was an ideal of perfection, never to be equalled in this defective world. Mankind had only to wonder that such excellence had ever been presented in a visible shape. Unless memory is very treacherous, we once in early youth saw [page 52b] on the walls of some country inn or lodging-house two coloured prints, respectively representing a young gentleman and lady in old-fashioned costume, and purporting to be Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy. We are even inclined to recollect that in those works of art an attempt was made to combine the effects of painting and sculpture by an extremely simple process not uncommon in the last century. The coloured figures were carefully cut out and pasted upon a black ground, but one of the arms was purposely left destitute of the adhesive material, and allowed to project forwards. If the figure was that of a lady, and the unstuck hand held a nosegay, the effect was considered by competent judges to be pretty and natural. What an instructive paper, by the way, might be written on the successive ornaments that have decorated the walls and mantelpieces of the less opulent classes during (say) the last hundred years! The record would be of quaint designs in worsted, of violently-coloured mezzotints traceable to the now forgotten establishment of Messrs. Bowles and Carver in St. Paul’s Churchyard, of horrid waxwork groups on scriptural subjects, of black velvet used as an imitation of the feline coat, of elder-pith and minute rolls of paper applied to the adornment of various unserviceable boxes—all objects that belonged to a past generation, and can never return save through a retrogression in taste that is scarcely to be considered possible.

Such a thing of the past is the

History of Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy, which, as we have seen, was most famous in its day. When a book, or an actor, or an event becomes the subject of a casual reference or of a cheap print, and that in an age when there are no illustrated newspapers hungering after appropriate topics, we may be assured that it was familiar to a very large number of persons, and that the knowledge of it was by no means confined to those of superior culture. We may assume that Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy were characters known to that large class of the public which in the last century certainly did not read much. That to the ears of many of our readers the names of interesting couple will have something of a familiar ring, we are inclined to believe. Still more strong is our opinion that the whole body of those who know of them any more than their names might easily be accommodated in a china-closet of moderate dimensions. Nay, having carefully, and with no small effort, read through the novel, we are ready to confess a certain complacent satisfaction at the circumstance that we are in possession of a modicum of erudition vouchsafed to almost none of our fellow creatures. We feel that it is simply a moral restraint which prevents us from indulging in the most reckless mendacity while describing Mrs. Eliza Haywood’s work, and that if we refrain from saying, for example, that Jemmy Jessamy is King James II., and Jenny Jessamy the Duchess of Marlborough in disguise, we are governed wholly by regard for truth, and not by any fear of detection in falsehood.

There is something very misleading both in the title of the novel and in the fact of its former popularity. There is a sort of affinity between the words “Jessamy” and “Jessamine” (or Jasmine), and there is a homely Anglicism in the “ Jemmy” and the “Jenny,” that lead one to expect a tale of pastoral love in which the insipidity of the ordinary Damon and Phyllis will be rendered additionally nauseous by an infusion of home-grown sentimentality. No one can be more fluent than your genuine Britisher in twaddling about the innocence of rural life. With this hypothesis deduced from the title-page of the book, the ingenious speculator may account for the rise and fall of the Jessamy mania. Once people liked stories about well-bred rustics who talked a great deal of highflown stuff, but they have long ceased to relish incitements of the sort. Jenny Jessamy was some village maiden, dishonourably courted by some wicked squire, who cruelly persecuted her proper lover, Jemmy. At last virtue triumphed, the squire was overthrown, and very probably Jemmy turned out to be the lawful owner of his wrongly-held estate. All very well in its time, but folks like something different now. Since the days of the old-fashioned romances they have been well fed with historical fictions, and, having become tired of them in their turn, have comfortably settled into a contemplation of modern actual life, viewed, just at present, under somewhat stormy aspects.

So much more plausible does this hypothesis look than many serious historical theories, that one feels a regret in demolishing it utterly with the declaration that never was a book less sentimental, less pastoral, or less obviously addressed to any transient caprice of the reading world than this same story of

Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy. The young gentleman is heir to a large estate, and has been duly educated at Eton and Oxford. The young lady, a distant cousin, is daughter of a wealthy merchant, and grows up a model of high-bred propriety. The respective parents of Jemmy and Jenny destine them for each other, and die, leaving them in a state of complete independence at an early age. They are expected by their acquaintance to marry immediately, but several instances of domestic unhappiness which come under their immediate notice determine them not to be too precipitate, Jenny being the leader on the road of wisdom. “Every one,” says that sage young maiden, “before they engage in marriage, should be well versed in all those things, whatever they are, which constitute the happiness of it; this town is an ample school, and both of us have acquaintance enough in it to learn, from the mistakes of others, how to regulate our own conduct and passions so as not to be laughed at ourselves for what we laugh at in them.” For these remarks she is well rewarded by Jemmy with the exclamation, “Spoken like a

philosophoress”! The [page 53a] instances of conjugal discomfort form the subjects of short episodes, the authoress throughout adopting the method which we find employed by Cervantes, Scarron, Le Sage, Fielding, Smollett, etc., of interweaving the main story with others sometimes scarcely connected with it. Generally the incidents narrated are not of a very exciting kind, though they sometimes illustrate a lax state of society. Here a married gentleman of distinction has a mistress in every respect inferior to his own wife; there a married lady of quality pays her gaming debts at the expense of her honour. More eccentric than these is a certain Lady Fisk, who “went to Covent Garden in man’s clothes, picked up a woman of the town, and was severely beaten by her on the discovery of her sex.” But the prevailing tone of the book is decidedly grave and moral, and, though there is more plain-speaking than at the present day, it is quite obvious that the authoress is never intentionally licentious.

When Jemmy and Jenny have wisely resolved to prepare them-selves for the marriage state, they are separated for some time, Jenny going to Bath with some friends of rank and position, whose mild adventures help to swell out the volumes, and Jemmy, through some business engagement, being constantly hindered from joining her. Though the young gentleman is somewhat of a libertine, and apt to indulge in transient amours, he never thinks of breaking his engagement with his dear Jenny, who, on her side, never indulges in jealousy. Her virtue, indeed, while of the purest quality, is at the same time of that robust kind that does not depend on innocence, and at little more than twenty years of age she can perfectly distinguish between the aimless peccadilloes of male unmarried youth and those aberrations that are likely to result in a breach of promise of marriage. The following little speech which she makes on one occasion to her Jemmy illustrates with singular plainness her general views on the subject of masculine constancy:

“Make no vows on this last head (fidelity) I beseech you. I have heard people much older and more experienced than ourselves say that the soonest [sic, for surest] way to do a thing is to resolve against it. Besides, my dear Jemmy,” added she, with the most engaging sprightliness, “I shall not be so unreasonable to expect more constancy from you than human nature and your constitution will allow; and if you are as good as you can, may very well content myself with your endeavours to be better.”

The only serious obstacle to the happiness of these lovers arises through the machinations of Bellpine, a false friend of Jemmy’s, who, having become enamoured of Jenny and her fortune, vainly tries to make Jemmy fall seriously in love with a certain Miss Chit, famed for the excellence of her singing, but is more successful in spreading a report of Jemmy’s serious inconstancy which reaches the ears of Jenny. When the machinations of Bellpine are discovered, he is so terribly mauled by the injured Jemmy, in single combat, that his life is despaired of, and the avenger flies to France to escape the consequences of too successful duelling. However, the wounded man recovers; Jenny, going as one of a wedding-party to Paris, joins the disconsolate Jemmy, and brings him back safe and sound to marry her in the “Abbey Church of Westminster.”

There is the whole story—that is to say, the main story, stripped of its details and ramifications. That in itself it is not “sensational,” will be at once perceived; let us hasten to state that nothing whatever is done to make it so. The personages part, meet again flirt, quarrel, faint, and fall into each other’s arms; but, do what they will, they no more lay claim to our sympathies than would a set of well-dressed and cleverly-managed puppets in a Fantoccini. We are told a great deal about love and hatred, but we never see them expressed. Of the art of representing an emotion, so as to kindle something corresponding in the mind of any reader of the present day, the authoress has not the slightest notion; and even when a passion is declared by one of the principal characters, we are convinced that the speaker is less concerned about his heart than about the rounding of his periods, though these are not very well rounded after all. Nor is any appeal made to the appreciation of wit and repartee, as in the writings of Congreve, and other heartless hierarchs of a peculiar worship of intellect. In the whole compass of three good-sized volumes there is not a smart saying that one would care to record as a specimen of superficial brilliancy.

At humour or at delineation of character no attempt is made. The personages all belong to the highest ranks of a very artificial society, lounge through their time in London and Bath, amuse one another with elaborate gallantries, and indulge in copious but not reckless verbosity. More pains are taken with Jenny’s character than with that of the others, but she is such a mere incarnation of the views entertained by the authoress that her speeches are scarcely to be distinguished from the moral exordia which are uttered by Mrs. Eliza Haywood, in her own person, at the commencement of many chapters.

Some of the personages, void of individuality as they all are, were possibly intended to adumbrate well-known realities of the day. Miss Chit, who attracts all the fashionable world by her excellent singing, and is supposed to have a father of higher station than her ostensible parent; Celandrine, a cowardly lady-killer, who ignominiously refuses a challenge at a period when a recognition of the old code of honour was implied in social morality; Lady Fisk, who gets into street rows—these might perhaps have been recognised by the readers of the middle of the last century as persons whose follies and vices were the subject of common talk. In her early days, Mrs. Haywood, who seems to have been born somewhere about 1693, and died in 1756, formed herself upon the more celebrated Mrs. Manley, and wrote two books—[53b] entitled the

Court of Carimania, and the

New Utopia—which owed their popularity to the quantity of scandal they contained, and caused Pope to bestow upon their authoress a few coarse lines in the

Dunciad, which, whatever might have been the provocation, were most disgraceful to the poet. When she wrote her later works, of which

Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy, attained the greatest celebrity, she had become a reformed character, and a most ostentatious preacher of such morality as was current at the time. But there is no reason to assume that she entirely left off her old habits, and altogether forbade herself the pleasure of writing a little harmless unobtrusive scandal at the expense of her acquaintance. If the cap did not fit, no harm was done; if it did, the reader was to be blamed for putting it on.

But what will most strike a modern thinker is the tone of wisdom in which Mrs. Haywood utters her ethical platitudes. It is hard to conceive the degree of

naïveté with which both writer and reader must have been endowed when passages like following were considered instructive:

Youth, beauty, and wit have deservingly a very powerful influence on [sic, for over] the human heart; and every day’s [sic, for day,] experience obliges us to own that wealth without the aid of any of these, is of itself sufficient to captivate; it supplies all other defects; it smooths the wrinkles of fourscore; it shapes deformity into comeliness, and gives graces to idiotism itself; as it is said by the inimitable Shakespeare:

Gold! yellow glittering precious gold!

Gold! that will make black white; foul fair; wrong right;

Base noble; old young; cowards valiant.

But when the gifts of nature are joined with those of fortune, how strong is the attraction! How irresistible is the force of such united charms! According to the words of the humorous poet—

Hence ’tis, no lover has the pow’r

T’enforce a desperate amour,

As he that has two strings to’s bow,

And burns for love and money too.

We ought not therefore, methinks, to judge with too much severity on the vanity of a fine lady; who seeing herself perpetually surrounded with a crowd of lovers, each endeavouring to excel all his rivals in the most extravagant demonstrations of affection, can hardly believe she deserves not some part, at least, of the admiration she receives. But what pretence soever we may make to excuse the weakness of exulting in a multiplicity of lovers, it is still a weakness which all imaginable care ought to be taken to subdue; as it may draw on the most fatal consequences both on the admirers and admired.

All this is sound and charitable enough, but one could scarcely find a more perfect specimen of the grave kind of twaddle. Let a fluent writer once choose his moral theory, and he may cover as many pages as there are lines in the above with a specious exhibition of wisdom that will scarcely require the most moderate expenditure of thought. The quotations from Shakespeare and Butler are singularly illustrative of the period at which the book was written. The old pedantic habit of overloading a text with citations from Greek and Latin authors crudely massed together, after the manner of Burton, had passed away, but far more celebrated writers than Mrs. Haywood show us that people in the middle of the last century had not learned clearly to distinguish between illustration and proof. If the fair Eliza can back up an opinion, which none but a lunatic would think of contradicting, with a distich from that great master of the human heart, Mr. Dryden, or with half a dozen lines from Cowley, “who was certainly as great a judge of love as was Ovid himself,” she feels that she has made assurance doubly sure.

With all the peculiarities which will seem so strange to a modern reader, the

History of Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy is by no means a contemptible book. The story is skillfully constructed, without sacrifice of probability, or recourse to claptrap of any kind; and if it never excites, it never becomes wholly devoid of interest. Moreover, it would be hard to find a more perfect specimen of that satisfaction with a thoroughly worldly and semi-Pagan morality which at a later period earned for the eighteenth century the epithet “Godless,” than in the rules of life laid in the course of this once famous novel.

*

The History of Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy. By Mrs. Haywood.