Finding Fabian's was a red-letter day for me as a collector: I came away from my first visit with two eighteenth century first editions at bargain prices: a somewhat worn copy of Macpherson’s Fingal (1762), the first part of his Ossain cycle, and a very nice set of Le Sage’s Gil Blas, as translated by Smollett (1750).

Sadly, despite his long tenure in such a prominent location, Fabian’s seems to have left almost no trace on the internet. In offering up some personal memories of Fabian (and Fabian’s shop) below, I am partly relying on my recollection of my 1990 visit, but I am also making use of some notes I made in 1993, after a return visit, which I only re-discovered during a clean-up last week.

A bright, clean travel agent now occupies 309 Swanston Street (photo above), which is opposite the State Library of Victoria; but for many years it was occupied by a rather different business: Fabian’s Fine Old Furniture. The eponymous owner, Fabian, was a rather eccentric, wild-haired man who had many interesting old books held in three or four massive Victorian book cases, while a goodly number more were liberally distributed in messy piles in various corners, nooks and crannies on the floor. Like the owner, the books, and the bookcases, the shop was old.

In the early 1990s, it had the sort of deep, dusty, brass edged, shop-front display-window that all the best second hand bookshops ought to have. On display in this window were china cups and saucers, Wisden Cricketers’ Almanacks, faded copper plate engravings and maps with labels such as: “This map is 256 years old!”—“This book 152 years old!”—all with exclamation marks, silently bellowing at the passing foot-traffic. I don’t know how often these labels caught the eye of any passer by—with so much dust on the windows the signs were hard to read—but I remember very few interruptions whenever I visited Fabian’s—and all my visits to Fabian’s were lengthy.

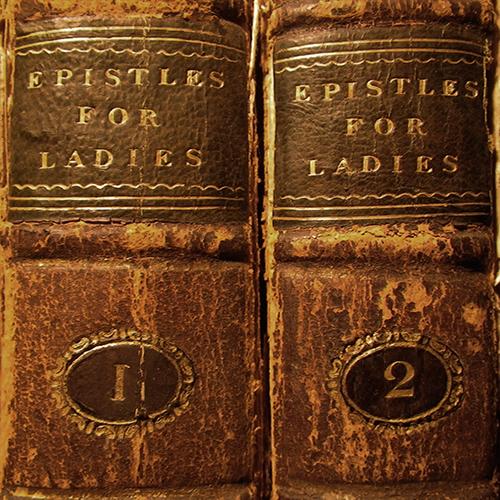

The reason for the length of my visits was because Fabian was an unashamed biblioclast. Fabian liked neatly bound sets of books, but it was his practice to keep the different volumes of any set of books equally distributed between the shelves of however many bookcases he had or—whenever he sold a bookcase—between the shelves of the remaining bookcases and in piles on the floor.

He distributed the books in this was because—he explained to me—he wanted each bookcase to display a variety of titles, that a complete set of books was unsightly, and that complete sets would be likely to frighten off prospective buyers. His pricing is worked out on a per-volume basis, and was calculated solely on the size of a volume and the nature of its binding. I paid $45 per volume for my 12mo set (Gil Blas) and $100 for my folio volume (Fingal), but I think $80 was normally the going rate, when part of a set.

Since Fabian did not care for completeness—in fact, he disliked it—but he liked neatly bound books, he had bought and distributed around his small shop many incomplete sets. As a result, even after an extensive, laborious search, neither buyer nor seller could be entirely sure that every volume that Fabian actually had in his shop had been found, unless the books thus collected together from all corners of the shop formed an unambiguously-complete set.

Incomplete sets might be incomplete because Fabian bought them that way, or they may have been incomplete because the buyer had overlooked an odd-volume. This created a moral problem for a fastidious book buyer like myself: how could you be sure that, in the process of buying all the volumes of a seemingly-incomplete set that you had managed to accumulate, after hours spent turning over thousands of books, you were not thereby breaking up a complete set that you had simply failed to find all the volumes for?

Fabian was, obviously, unconcerned about this. Indeed, it seemed as if this sort of “accidental” breaking up of a set suited Fabian, the remaining volumes presented a more varied face to the buyer, and it made it easier for him to dispose of the remaining odd volumes.

Since I am a completist, I would spend hours patiently accumulating volumes of any and all sets that I was interested in; slowly building up piles of matching volumes. When—as was more often the case than not—I failed to find a complete set, I would leave without the books, and Fabian would re-distribute the volumes around the shop, according to whatever principle of aesthetics that drove him. A year or so later I would return, and go through the process again.

Eventually, despite the appeal of thousands of old, beautifully bound books, and the prosepect of a repeat of my 1990 success, I was worn down by my actual lack of success in finding anything that was new-to-stock or complete, and so I stopped visiting his shop. From the mid-90s, for about a decade after I moved to Melbourne I would regularly see Fabian on a Sandringham-line train, with his distinctive wild grey-white hair, on his way into or out of the city. I would seem at different times of the day, either on his way in or out, so I gather that, in old age, he simply went in whenever he felt like it. (There were no opening hours advertised on his shop, and it was often closed when I visited.)

* * * * *

Returning to 1993: a friend and I were occupied in the doomed process of uncovering the companion volumes of an early set of Smollett’s Peregrine Pickle and The Works of Madame de Genlis, ignoring Fabian’s protest that the set was probably never complete to begin with and fearing that, if it had been complete, he had probably rendered it otherwise long since due to his practice of selling off volumes at random, when a well-dressed young man came into the shop, drew the attention of Fabian, and left us to our dusty work.

The conversation began, as I recorded it, in the following fashion:

FABIAN: Hello. Can I help you?

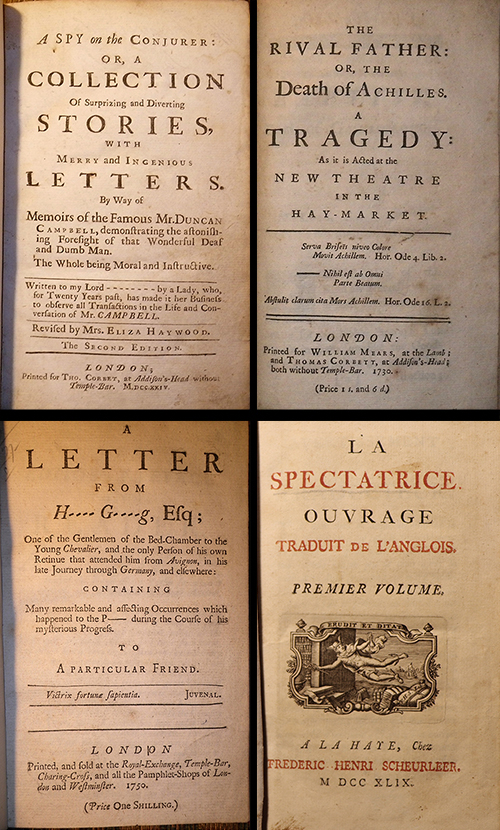

VISITOR: Yes. I’ve bought an old table that I want to put a bit of a display on, y’know, and what I wanted was some old books. I’ve got a bit of a shelf, and some things, vases and things like that, too, but what I need is a few antique books to put on it. ’Bout four of them. It doesn’t matter what’s in them because I’m never going to look in them [this said emphatically] as long as they are old, and look good, like these [indicating a set I was accumulating of The Works of Hobbes].

FABIAN: Yes, well, I get quite a lot of people coming in who want books like you do, for display; I have lots of old books here, with old leather bindings, all sorts of sizes and colours, and prices, so I am sure to have something that will suit. Now, about how much did you want to spend?

There followed a discussion concerning how much the Visitor wished to spend, whether he preferred brown to black covers and so forth. Books in French or Latin, were offered, Fabian did his best to sell his books (“Now this one here is nearly a quarter of a thousand years old! Well, that’s older than the settlement in Australia”) and, at one memorable juncture, when Fabian was showing the Visitor a random selection of four of the twelve volumes of a Latin edition of the proceedings of the Council of Trent, the Visitor, admiring the binding, and in response to Fabian’s explanation of what the book was about, said “of course, I could always learn Latin if I bought them, and then I could read them.”

As I mentioned above, customers were rare; the shop was quiet, and the conversation struck a cord—I had recently read W. J. West’s The Strange Rise of Semi-Literate England (1991)—so I made notes as soon as I left the shop and recorded the details as well as I could soon after. Unfortunately, I did not make a note of whether the well-dressed young man bought any volumes of the proceedings of the Council of Trent. Even if he had, we will never know whether, by doing so, he was prompted to [1] learn Latin and then [2] immediately sit down to read his books, but I think it is very unlikely.