According to this article, a survey of 1,863 people conducted in Britain this week suggests many e-book readers feel "freed" by the device to read books they would otherwise feel embarrassed about reading.

The MyVoucherCodes.co.uk survey indicates that

• 58% of people use the device to "hide" what they are reading

• 57% were hiding "children’s books"

• 34% were hiding erotic novels

• 26% were hiding sci-fi books

So, all but 1% who hid books, hid YA fiction (I am guessing it is YA fiction, not children's books like The Cat in the Hat since they say "children’s books, such as Harry Potter"), but only about half of those who hid books hid erotica or sci-fi.

From which we can gather that admitting to reading YA fiction is a bigger social faux pas than reading porn or sci-fi: that there is a stronger stigma associated with reading Harry Potter and The Hunger Games. Or perhaps, that readers of YA fiction are, in general, a much more furtive lot. Sneaky. Secretive.

But to continue:

An earlier poll of British readers found that a third of ebook readers are too embarrassed to reveal the truth about what they are reading. One in five said they would be so ashamed of their collection that if they were to lose their ebook reader they would not claim it back. But the results also showed that 71 per cent of books on the shelves of those who responded were autobiographies, political memoirs, and other non-fiction titles—but those categories accounted for just 14 per cent of e-books read by those surveyed.

(I think the word other could safely be dropped from the last sentence.)

So, 20% of e-book users are so ashamed of reading YA fiction/porn/sci-fi that they would pay a couple of hundred dollars to buy a new reader, rather than admit this deeply embarrassing fact. It would be interesting to know whether the same were true of non-e-book readers

Are 20% of all readers so anxious about being outed as YA fiction/porn/sci-fi readers? Or, are e-book readers, as a group, much more concerned what other people think about them, about the impression they are giving sitting, with their e-book reader in their lap, in front of shelves of political memoirs and non-fiction titles. Are they superficial, but vulnerable, poseurs?

For the record: I am presently re-reading The Hunger Games, spent three years studying erotica (and got to call it "research") and spent the best part of a decade reading nothing but sci-fi and horror. But then, I don't have a e-book reader.

Monday, 28 May 2012

Sunday, 27 May 2012

The Mothers of the Novel Series

Pandora's "Mothers of the Novel" series was either prompted by, or promoted by—and with—Dale Spender's Mothers of the Novel: 100 good women writers before Jane Austen.

There are twenty novels in the series, printed in paperback, with a distinctive cover illustration by Marion Dalley, between 1986 and 1989. (Only sixteen are listed on Wikipedia here but all twenty were listed on Library Thing by christiguc in September of 2008.) My list is below.

There are different ways of listing the MotN novels: alphabetical, by author, date of original publications, date of republication, and ISBN order. I have opted for date of original publications because my main interest coincides with Spender's sub-title ("100 good women writers before Jane Austen").

Jane Austen's first published novel was Sense and Sensibility (1811) so my first interest is "which novels in this series were published (or written, I guess) before 1811?" As you can see further below, the answer is only the first fifteen because this series contains novels printed as late as 1834.

The 1834 text is Maria Edgeworth's final novel, Helen: I think it, and Maria Edgeworth's other novels, should also have been excluded from the series on the basis that they had been reprinted in the nineteenth century with reasonable regularity and were, therefore, accessible to readers interested in women writers "before Jane Austen." (Macmillan included five novels in its Carnford series and these beautiful books were reprinted in pocket format in the 1920s.)

Personally, I would also have excluded all of Mary Brunton's and Lady Morgan's novels too, because one of each autor's works post-date 1811 too, but the real reason is I'd like to have seen more of the early eighteenth-century novels …

I bought my copy of Spender's Mothers of the Novel on 11 November 1991 and had read it eight days later. Before finishing it I had bought two of the novels in the series (Sheridan's Memoirs of Miss Sidney Biddulph and Smith's The Old Manor House) and I bought another two in the following few weeks: Brunton's Discipline and Haywood's History of Miss Betsy Thoughtless—my first book by Haywood.

Looking back over my diary of purchases: I see that I bought 109 books in the month following 9 November. These include eighteenth-century novels (Burney's Cecilia and Evelina, Fielding's The Adventures of David Simple and Wollstonecraft's Mary), but also a stack of Austen, Eliot and Woolf, and I also snapped up Ellen Moers's Literary Women and Roger Lonsdale's Eighteenth-Century Women Poets.

All this book-buying is simply a reflection of a rapidly-growing enthusiasm for eighteenth-century literature, early women writers and feminist literary scholarship. I bought Spender because I was already interested in all three subjects, but Mothers of the Novel gave a focus to my interest. And so, when I was looking around for a suitable PhD topic a few years, later I returned to Mothers of the Novel for inspiration.

At first, I thought I would test Spender's thesis: that one hundred women writers had been tremendously popular before Jane Austen but had since been overlooked by a sexist literary establishment. Or rather, which women writers had been tremendously popular before Jane Austen, before they had been overlooked by a sexist literary establishment.

I was going to do this by combing every eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century biographical dictionary and work of nascent literary scholarship to see which women had been highly regarded in the eighteenth century. (I still have the list of names: who was in the dictionaries etc, who wasn't.)

I quickly realised that many (most?) of the "good women writers before Jane Austen" had not been recognised as such in the eighteenth century. The opposite, in fact, seemed to be true. Whatever their popularity, these "good women writers" were despised. So my next thought was choosing a group of these despised writers and tracking their fortunes: their popularity and critical reception.

I narrowed my long list down to three: "the fair triumvirate of wit". Amazingly, there is a Wikipedia page on this phrase (here) which explains: "The fair triumvirate of wit refers to the three 18th century authors Eliza Haywood, Delarivier Manley, and Aphra Behn."

Regualr readers of this blog will know what happened next: I started on Haywood, realised that if I were to do a proper study of her popularity and reception I'd need to do a full bibliography to establish what, in fact, she had written and how often her works had been reprinted. My scholarship money ran out after three and a half years. My bibliography/PhD took ten.

When my Bibliography of Eliza Haywood was published I dedicated it to Spender—despite the fact that, by then, I knew that Spender was wrong about many of the things she had to say on Haywood. Still, without the fire she put in my belly with her Mothers of the Novel in November 1991 I would not have been able to put up with all the crap that goes with being a doctoral candidate for a decade.

(On this subject I often feel like quoting Johnson's letter to Chesterfield, particularly the famous tricolon: "The notice which you have been pleased to take of my labours, had it been early, had been kind; but it has been delayed till I am indifferent, and cannot enjoy it: till I am solitary, and cannot impart it; till I am known, and do not want it. I hope it is no very cynical asperity not to confess obligations where no benefit has been received, or to be unwilling that the public should consider me as owing that to a patron, which providence has enabled me to do for myself." The fit is awkward but it is probably better if I do not explain the application.)

Returning to Spender's Mothers of the Novel: the back cover of my copy contains a list of fifteen titles in the "Mothers of the Novel" series (here). This list puzzled me, since it was not in alphabetical order, by author or title, or date of original publications. It turns out that these fifteen titles are in the sequence they appeared in the MotN series, which is more-or-less the sequence of ISBNs. I am sure that made sense to Pandora …

And so, at the risk of confusing any visitors to this site, here is my list of all twenty MotN titles, in chronological order according to the original date of publication:

MotN no.01 Sarah Fielding, The Governess, or The Little Female Academy (1749; repr. 1987) [ISBN 0-86358-182-X].

MotN no.02 Eliza Haywood, The History of Miss Betsy Thoughtless (1751; repr. 1986) [ISBN 0-86358-090-4].

MotN no.03 Charlotte Lennox, The Female Quixote, or the Adventures of Arabella (1752; repr. 1986) [ISBN 0-86358-080-7].

MotN no.04 Frances Sheridan, Memoirs of Miss Sidney Bidulph (1761; repr. 1987) [ISBN 0-86358-134-X].

MotN no.05 Mary Hamilton, Munster Village (1778; repr. 1987) [ISBN 0-86358-133-1].

MotN no.06 Charlotte Smith, Emmeline: The Orphan of the Castle (1788; repr. 1989) [ISBN: 0-86358-264-8].

MotN no.07 Elizabeth Inchbald, A Simple Story (1791; repr. 1987) [ISBN 0-86358-136-6].

MotN no.08 Charlotte Smith, The Old Manor House (1793; repr. 1987) [ISBN 0-86358-135-8].

MotN no.09 Eliza Fenwick, Secrecy, or The Ruin of the Rock (1795; repr. 1988) [ISBN 0-86358-307-5].

MotN no.10 Mary Hays, The Memoirs of Emma Courtney (1796; repr. 1987) [ISBN 0-86358-132-3].

MotN no.11 Harriet and Sophia Lee, The Canterbury Tales (1797–1805; repr. 1989) [ISBN: 0-86358-308-3]

MotN no.12 Maria Edgeworth, Belinda (1801; repr. 1986; repr. 1987) [ISBN 0-86358-074-2].

MotN no.13 Amelia Opie, Adeline Mowbray, or The Mother and Daughter (1804; repr. 1986) [ISBN 0-86358-085-8].

MotN no.14 Lady Morgan [Sydney Owenson], The Wild Irish Girl (1806; repr. 1986) [ISBN 0-86358-097-1].

MotN no.15 Mary Brunton, Self-control (1810/11; repr. 1986) [ISBN 0-86358-084-X].

MotN no.16 Maria Edgeworth, Patronage (1814; repr. 1986) [ISBN 0-86358-106-4].

MotN no.17 Fanny Burney, The Wanderer; or Female Difficulties (1814; repr. 1988) [ISBN 0-86358-263-X]

MotN no.18 Mary Brunton, Discipline (1815; repr. 1986) [ISBN 0-86358-105-6].

MotN no.19 Lady Morgan [Sydney Owenson], The O’Briens and the O’Flahertys: A National Tale (1827; repr. 1988) [ISBN: 0-86358-289-3].

MotN no.20 Maria Edgeworth, Helen (1834; repr. 1987) [ISBN 0-86358-104-8].

[MotN no.9; rear cover here]

[UPDATE: 2 July 2016: After all my pictures disappeared again I decided to give up on external hosts for large versions (1000px) of my image files and, for now on, will stick with the smaller images (500px), which Blogger is prepared to host.]

[Spender's MotN; rear cover here]

There are twenty novels in the series, printed in paperback, with a distinctive cover illustration by Marion Dalley, between 1986 and 1989. (Only sixteen are listed on Wikipedia here but all twenty were listed on Library Thing by christiguc in September of 2008.) My list is below.

There are different ways of listing the MotN novels: alphabetical, by author, date of original publications, date of republication, and ISBN order. I have opted for date of original publications because my main interest coincides with Spender's sub-title ("100 good women writers before Jane Austen").

Jane Austen's first published novel was Sense and Sensibility (1811) so my first interest is "which novels in this series were published (or written, I guess) before 1811?" As you can see further below, the answer is only the first fifteen because this series contains novels printed as late as 1834.

The 1834 text is Maria Edgeworth's final novel, Helen: I think it, and Maria Edgeworth's other novels, should also have been excluded from the series on the basis that they had been reprinted in the nineteenth century with reasonable regularity and were, therefore, accessible to readers interested in women writers "before Jane Austen." (Macmillan included five novels in its Carnford series and these beautiful books were reprinted in pocket format in the 1920s.)

Personally, I would also have excluded all of Mary Brunton's and Lady Morgan's novels too, because one of each autor's works post-date 1811 too, but the real reason is I'd like to have seen more of the early eighteenth-century novels …

* * * * *

I bought my copy of Spender's Mothers of the Novel on 11 November 1991 and had read it eight days later. Before finishing it I had bought two of the novels in the series (Sheridan's Memoirs of Miss Sidney Biddulph and Smith's The Old Manor House) and I bought another two in the following few weeks: Brunton's Discipline and Haywood's History of Miss Betsy Thoughtless—my first book by Haywood.

Looking back over my diary of purchases: I see that I bought 109 books in the month following 9 November. These include eighteenth-century novels (Burney's Cecilia and Evelina, Fielding's The Adventures of David Simple and Wollstonecraft's Mary), but also a stack of Austen, Eliot and Woolf, and I also snapped up Ellen Moers's Literary Women and Roger Lonsdale's Eighteenth-Century Women Poets.

All this book-buying is simply a reflection of a rapidly-growing enthusiasm for eighteenth-century literature, early women writers and feminist literary scholarship. I bought Spender because I was already interested in all three subjects, but Mothers of the Novel gave a focus to my interest. And so, when I was looking around for a suitable PhD topic a few years, later I returned to Mothers of the Novel for inspiration.

At first, I thought I would test Spender's thesis: that one hundred women writers had been tremendously popular before Jane Austen but had since been overlooked by a sexist literary establishment. Or rather, which women writers had been tremendously popular before Jane Austen, before they had been overlooked by a sexist literary establishment.

I was going to do this by combing every eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century biographical dictionary and work of nascent literary scholarship to see which women had been highly regarded in the eighteenth century. (I still have the list of names: who was in the dictionaries etc, who wasn't.)

I quickly realised that many (most?) of the "good women writers before Jane Austen" had not been recognised as such in the eighteenth century. The opposite, in fact, seemed to be true. Whatever their popularity, these "good women writers" were despised. So my next thought was choosing a group of these despised writers and tracking their fortunes: their popularity and critical reception.

I narrowed my long list down to three: "the fair triumvirate of wit". Amazingly, there is a Wikipedia page on this phrase (here) which explains: "The fair triumvirate of wit refers to the three 18th century authors Eliza Haywood, Delarivier Manley, and Aphra Behn."

Regualr readers of this blog will know what happened next: I started on Haywood, realised that if I were to do a proper study of her popularity and reception I'd need to do a full bibliography to establish what, in fact, she had written and how often her works had been reprinted. My scholarship money ran out after three and a half years. My bibliography/PhD took ten.

When my Bibliography of Eliza Haywood was published I dedicated it to Spender—despite the fact that, by then, I knew that Spender was wrong about many of the things she had to say on Haywood. Still, without the fire she put in my belly with her Mothers of the Novel in November 1991 I would not have been able to put up with all the crap that goes with being a doctoral candidate for a decade.

(On this subject I often feel like quoting Johnson's letter to Chesterfield, particularly the famous tricolon: "The notice which you have been pleased to take of my labours, had it been early, had been kind; but it has been delayed till I am indifferent, and cannot enjoy it: till I am solitary, and cannot impart it; till I am known, and do not want it. I hope it is no very cynical asperity not to confess obligations where no benefit has been received, or to be unwilling that the public should consider me as owing that to a patron, which providence has enabled me to do for myself." The fit is awkward but it is probably better if I do not explain the application.)

* * * * *

Returning to Spender's Mothers of the Novel: the back cover of my copy contains a list of fifteen titles in the "Mothers of the Novel" series (here). This list puzzled me, since it was not in alphabetical order, by author or title, or date of original publications. It turns out that these fifteen titles are in the sequence they appeared in the MotN series, which is more-or-less the sequence of ISBNs. I am sure that made sense to Pandora …

And so, at the risk of confusing any visitors to this site, here is my list of all twenty MotN titles, in chronological order according to the original date of publication:

MotN no.01 Sarah Fielding, The Governess, or The Little Female Academy (1749; repr. 1987) [ISBN 0-86358-182-X].

MotN no.02 Eliza Haywood, The History of Miss Betsy Thoughtless (1751; repr. 1986) [ISBN 0-86358-090-4].

MotN no.03 Charlotte Lennox, The Female Quixote, or the Adventures of Arabella (1752; repr. 1986) [ISBN 0-86358-080-7].

MotN no.04 Frances Sheridan, Memoirs of Miss Sidney Bidulph (1761; repr. 1987) [ISBN 0-86358-134-X].

MotN no.05 Mary Hamilton, Munster Village (1778; repr. 1987) [ISBN 0-86358-133-1].

MotN no.06 Charlotte Smith, Emmeline: The Orphan of the Castle (1788; repr. 1989) [ISBN: 0-86358-264-8].

MotN no.07 Elizabeth Inchbald, A Simple Story (1791; repr. 1987) [ISBN 0-86358-136-6].

MotN no.08 Charlotte Smith, The Old Manor House (1793; repr. 1987) [ISBN 0-86358-135-8].

MotN no.09 Eliza Fenwick, Secrecy, or The Ruin of the Rock (1795; repr. 1988) [ISBN 0-86358-307-5].

MotN no.10 Mary Hays, The Memoirs of Emma Courtney (1796; repr. 1987) [ISBN 0-86358-132-3].

MotN no.11 Harriet and Sophia Lee, The Canterbury Tales (1797–1805; repr. 1989) [ISBN: 0-86358-308-3]

MotN no.12 Maria Edgeworth, Belinda (1801; repr. 1986; repr. 1987) [ISBN 0-86358-074-2].

MotN no.13 Amelia Opie, Adeline Mowbray, or The Mother and Daughter (1804; repr. 1986) [ISBN 0-86358-085-8].

MotN no.14 Lady Morgan [Sydney Owenson], The Wild Irish Girl (1806; repr. 1986) [ISBN 0-86358-097-1].

MotN no.15 Mary Brunton, Self-control (1810/11; repr. 1986) [ISBN 0-86358-084-X].

MotN no.16 Maria Edgeworth, Patronage (1814; repr. 1986) [ISBN 0-86358-106-4].

MotN no.17 Fanny Burney, The Wanderer; or Female Difficulties (1814; repr. 1988) [ISBN 0-86358-263-X]

MotN no.18 Mary Brunton, Discipline (1815; repr. 1986) [ISBN 0-86358-105-6].

MotN no.19 Lady Morgan [Sydney Owenson], The O’Briens and the O’Flahertys: A National Tale (1827; repr. 1988) [ISBN: 0-86358-289-3].

MotN no.20 Maria Edgeworth, Helen (1834; repr. 1987) [ISBN 0-86358-104-8].

* * * * *

[MotN no.1; rear cover here]

[MotN no.2; rear cover here]

[MotN no.3; rear cover here]

[MotN no.4; rear cover here]

[MotN no.5; rear cover here]

[MotN no.6; rear cover here]

[MotN no.7; rear cover here]

[MotN no.8; rear cover here]

[MotN no.9; rear cover here]

[MotN no.10; rear cover here]

[MotN no.11; rear cover here]

[MotN no.12; rear cover here]

[MotN no.13; rear cover here]

[MotN no.14; rear cover here]

[MotN no.15; rear cover here]

[MotN no.16; rear cover here]

[MotN no.17; rear cover here]

[MotN no.18; rear cover here]

[MotN no.19; rear cover here]

[MotN no.20; rear cover here]

[UPDATE: 2 July 2016: After all my pictures disappeared again I decided to give up on external hosts for large versions (1000px) of my image files and, for now on, will stick with the smaller images (500px), which Blogger is prepared to host.]

Labels:

18C,

19C,

Eliza Haywood,

Publishing

Wednesday, 23 May 2012

The Centre for the Book at Monash

I was recently asked by Dr Stephen Herrin, Rare Books Assistant Librarian, to write the Preface to an exhibition entitled "Books Never Die: An Exhibition on the History of the Book" (see here). While I was writing it I wanted to say a few words about the study of Book History at Monash and it occurred to me it was time to do a post on the subject here. It has been difficult piecing together information on the subject so I will do what I can now and correct, update or add information as it comes to hand.

Since 1982, The Centre for the Book has existed, at different times, under changing University (1982–84), Faculty (1985–97), Department (1998), and School (1999–) management. The Centre for the Book was reconstituted as a School of English, Communications and Performance Studies "research unit" in 2010. The management of all research units at Monash is in flux and so the future of the Centre for the Book is unclear. Again. But to look backwards …

In terms of name, as far as I can tell, The Centre for Bibliographical and Textual Studies existed from 1982 until 1998, when it was re-named The Centre for the Book. Apparently, Monash is unhappy about the liberal use of the term centre across the university, and there was some suggestion in 2009 that the name would have to be changed in 2010, but fortunately this did not happen.

As I said, the Centre for the Book is presently a research unit in the School of English, Communications and Performance Studies (ECPS; 2005–), previously the School of Literary, Visual and Performance Studies (LVPS; 1999–2005), which was formed in 1999 from an amalgamation of two departments (including English) and three centres (including the CftB).

(It is unclear whether the recent amalgamation, and renaming, of the English Department to create the "Literature Section" will force another name-change on the School—ECPS being the "School of English…" etc.)

Wal Kirsop was the "Chairman of the Committee for the Centre" from 1982 to 1991, then it was Ross Harvey (1992–93); Bryan Coleborne (1994–96); Harold Love (1997); Wal Kirsop (1998–2009). In 2010 Simone Murray became the Director of the Centre and in 2012 Anna Polletti and I became Co-Directors.

The Centre is the institutional body that represents bibliographers and book historians at Monash, but Monash had an active group of researchers in this field before the Centre was formed in 1982. (Wal Kirsop provided some details about this period, including the roles of Roger Laufer, Harold Love, Arthur Brown, Clive Probyn, Mary Lord etc, which I posted here.)

Monash academics (especially Wal Kirsop and Harrold Love) were instrumental in the establishment of the Bibliographical Society of Australia and New Zealand (BSANZ) in February 1969. Indeed, Wal was both a foundation-member of the BSANZ and its foundation-President (from 1969-73). And, as Brian McMullin noted recently, the journals published by BSANZ:

[have had] an Australian emphasis: within Australia it has had a Melbourne emphasis, and within Melbourne a Monash University emphasis, in that Monash has supplied several of the editors (among them two of its graduates) and has been the institutional home of what might be seen as a disproportionate number of its authors (B. J. McMullin, "Forty Years On" Script and Print 35:2 (2011): 106–7)

Since Brian does not enumerate the BSANZ Bulletin and Script & Print editors, I will do so, with details of which issues were edited by each editor where I have that information

Harold Love [staff] (vol.1, no.1–vol.2, no.3; March 1970–December 1975)

Brian McMullin [staff] (vol.2, no.4–vol.7, no.2; August 1976–July 1983)

Brian Hubber [Graduate], John Arnold [Graduate], Richard Overell [staff] (1993)

Ross Harvey [staff] (1995?)

Ian Morrison [Graduate] (vol.24, no. 3—vol.27, no.4; 2000–2003)

Patrick Spedding [Graduate] (vol.30–33; 2006–8)

As you can see, there are more than two Monash graduates in this list.

The Graduate School of Librarianship was established at Monash in 1976, offering masters courses in book history shortly thereafter. The Ancora Press and a weekly seminar series were immediately established by Jean Whyte. Thanks to Brian McMullin—a foundation lecturer—I have recordings of some of these early seminars, which suggest the scope of the series:

1. John Spring, "The Use of Type-Evidence in the Identification of the Work of Joseph Bennett, A Printer of the Restoration" (27 February 1976), [39.18 mins]

2. Wallace Kirsop, "On Pierre Corneille's Le Cid" (22 April 1976) [46.03 mins]

3. David Bradley and B. J. McMullin, "Textual Problems and Playhouse Copy; Consideration of Some Editorial Orthodoxies" (23 July 1976) [1hr 59.45 mins]

4. Angus Martin, "Specialized Retrospective Checklists: the example of eighteenth-century French Fiction" (8 Oct 1976) [1hr 38.05 mins]

5. Wallace Kirsop, "Bibliographical Detection" (14 October 1977) [1hr 03.07 mins]

From the above it appears that much of the energy of Harold and Wal went into establishing the BSANZ in the early 70s, and that it was only after they had been joined by Brian and others at Monash that the idea of a research Centre at Monash was seriously contemplated.

I am told that in the very early 1980s the Fraser Government proposed establishing ten research centres across Australia. A proposal was hastily assembled by Harold and Brian (Wal was in Cambridge at the time) for a Centre for Bibliographical and Textual Studies at Monash to undertake research for the Early Imprint Project** and to prepare scholarly editions. The Centre was unsuccessful in its bid, but redirected its proposal to the University (sans the request for money), and it was accepted.

Wal and Brian had been responsible for editing all issues of the BSANZ Bulletin from 1970 until this time. Shortly after the Centre was established (in 1982) the editorship was passed on to Trevor Mills (in 1983), allowing Brian and others at Monash to concentrate on Centre activities—including the development of an the interdisciplinary MA in Bibliographical and Textual Studies (restructured in 1994, but was still available in 2001).

Although, I am told, there were few graduates of the Monash "Master of Arts, Centre for Bibliographical and Textual Studies", I have been able to identify four students who produced important work between 1989 and 1999:

1. Linley Horrocks, "The creation of the Anzac market 1914-1918: the role of the press and the book trade" (MA thesis, 1989).

2. John Arnold, "The Fanfrolico Press: history and bibliography" (MA thesis, 1994). ¶ John's Fanfrolico Press: Satyrs, Fauns & Fine Books (Private Libraries Association, 2009) was reviewed by Nathan Garvey in Script & Print 36.2 (2012).

3. Laurel J. Clark, "Aspects of Melbourne book trade history: innovation and specialisation in the careers of F.F. Bailliere and Margareta Webber" (MA thesis, 1997).

4. Peter Pereyra, "Crime-fiction: from publisher to reader" (MA thesis, 1999).

Some significant work—both published and in theses—has also come out of both the "Bibliography and Textual Scholarship" unit and the "Analytical and Descriptive Bibliography" unit, which was offered by the Centre as an elective to M.A., M.Lib. and a few other candidates. This includes:

1. Annemie Gilbert and Sylvia Ransom, "The Imposition of Eighteenmos in Sixes, With Special Reference to Tranchefiles" BSANZ Bulletin 4:4 (1980), 269–75.

2. Penny McCristal, " '$½’ as a statement of signing" BSANZ Bulletin 19:3 (1995), 209–12.

By the time that the Centre was reconstituted in 2010 the principle academics involved in its earlier history had all retired and it was no longer possible for the remaining (emeritus) staff associated with the Centre to teach or take on higher-degree student supervisions. In the eyes of the university, this was a serious problem.

Of course, the Centre remained active in its research and publishing programme, in an academic seminar series, and in obtaining grant funding. And Wal and Brian took an active role in mentoring scholars like myself. (Without the assistance of Wal, Brian and others associated with the Centre, I would never have been able to take on the editorship of Script and Print and get it back up to date in such a short period.)

But, when all ECPS research units were reconstituted in 2010 as research-only units, the Centre needed a director with an outstanding research record who could supervise MA and PhD students. This was Simone.

Interestingly, teaching was specifically excluded from the purview of the new research units, although mentoring—and building the number of—M.A. and Ph.D. students were each among the KPIs. But with the recent university-wide move to force a coursework component on all MA and PhD students—it may be that research units will have some involvement with teaching in future. If so, there is a slight chance that some sort of Centre for the Book unit will be available to MA and PhD students again.

(A brief explanation: All research units and all new MA and PhD students will be administered within a program which is aligned with Field of Research codes (such as 2005–Literary Studies), by a program-manager, and will be supervised by Monash Institute of Graduate Research-approved, research-active staff, affiliated with that program. It seems likely that MA and PhD students will be offered coursework units that are aligned—at least to a certain extent—with the focus of research units within each program. If so, it seems likely that staff in the research units within each program will be called on to do the coursework teaching, as well as the supervision.)

Whether or not research units return to coursework teaching, the Centre for the Book at Monash has a small group of talented PhD students associated with it already and a steady stream of enquiries from would-be students suggests that this group will continue to grow.

**The aim of the Early Imprint Project (subsequently the Australian Book Heritage Resources Project) was to compile a short-title catalogue "in machine readable form" of all books published before 1801 held in Australasian libraries. See B. J. McMullin, "The Australia and New Zealand Early Imprints Project: The Background" BSANZ Bulletin 6:4 (1982), 163–73.

Bryan Coleborne, Chairman of the Committee for the Centre from 1994–96, records some of his thoughts about both the centre and the future of teaching bibliography and book history in his "Course Design and Analytical Bibliography" BSANZ Bulletin 20:3 (1996), 213–17.

Brian McMullin records some of his thoughts in "Bibliography in the Library School at Monash" BSANZ Bulletin 20:3 (1996), 218–20; "Forty Years On" Script and Print 35:2 (2011): 106–7.

* * * * *

Since 1982, The Centre for the Book has existed, at different times, under changing University (1982–84), Faculty (1985–97), Department (1998), and School (1999–) management. The Centre for the Book was reconstituted as a School of English, Communications and Performance Studies "research unit" in 2010. The management of all research units at Monash is in flux and so the future of the Centre for the Book is unclear. Again. But to look backwards …

In terms of name, as far as I can tell, The Centre for Bibliographical and Textual Studies existed from 1982 until 1998, when it was re-named The Centre for the Book. Apparently, Monash is unhappy about the liberal use of the term centre across the university, and there was some suggestion in 2009 that the name would have to be changed in 2010, but fortunately this did not happen.

As I said, the Centre for the Book is presently a research unit in the School of English, Communications and Performance Studies (ECPS; 2005–), previously the School of Literary, Visual and Performance Studies (LVPS; 1999–2005), which was formed in 1999 from an amalgamation of two departments (including English) and three centres (including the CftB).

(It is unclear whether the recent amalgamation, and renaming, of the English Department to create the "Literature Section" will force another name-change on the School—ECPS being the "School of English…" etc.)

Wal Kirsop was the "Chairman of the Committee for the Centre" from 1982 to 1991, then it was Ross Harvey (1992–93); Bryan Coleborne (1994–96); Harold Love (1997); Wal Kirsop (1998–2009). In 2010 Simone Murray became the Director of the Centre and in 2012 Anna Polletti and I became Co-Directors.

* * * * *

The Centre is the institutional body that represents bibliographers and book historians at Monash, but Monash had an active group of researchers in this field before the Centre was formed in 1982. (Wal Kirsop provided some details about this period, including the roles of Roger Laufer, Harold Love, Arthur Brown, Clive Probyn, Mary Lord etc, which I posted here.)

Monash academics (especially Wal Kirsop and Harrold Love) were instrumental in the establishment of the Bibliographical Society of Australia and New Zealand (BSANZ) in February 1969. Indeed, Wal was both a foundation-member of the BSANZ and its foundation-President (from 1969-73). And, as Brian McMullin noted recently, the journals published by BSANZ:

[have had] an Australian emphasis: within Australia it has had a Melbourne emphasis, and within Melbourne a Monash University emphasis, in that Monash has supplied several of the editors (among them two of its graduates) and has been the institutional home of what might be seen as a disproportionate number of its authors (B. J. McMullin, "Forty Years On" Script and Print 35:2 (2011): 106–7)

Since Brian does not enumerate the BSANZ Bulletin and Script & Print editors, I will do so, with details of which issues were edited by each editor where I have that information

Harold Love [staff] (vol.1, no.1–vol.2, no.3; March 1970–December 1975)

Brian McMullin [staff] (vol.2, no.4–vol.7, no.2; August 1976–July 1983)

Brian Hubber [Graduate], John Arnold [Graduate], Richard Overell [staff] (1993)

Ross Harvey [staff] (1995?)

Ian Morrison [Graduate] (vol.24, no. 3—vol.27, no.4; 2000–2003)

Patrick Spedding [Graduate] (vol.30–33; 2006–8)

As you can see, there are more than two Monash graduates in this list.

* * * * *

The Graduate School of Librarianship was established at Monash in 1976, offering masters courses in book history shortly thereafter. The Ancora Press and a weekly seminar series were immediately established by Jean Whyte. Thanks to Brian McMullin—a foundation lecturer—I have recordings of some of these early seminars, which suggest the scope of the series:

1. John Spring, "The Use of Type-Evidence in the Identification of the Work of Joseph Bennett, A Printer of the Restoration" (27 February 1976), [39.18 mins]

2. Wallace Kirsop, "On Pierre Corneille's Le Cid" (22 April 1976) [46.03 mins]

3. David Bradley and B. J. McMullin, "Textual Problems and Playhouse Copy; Consideration of Some Editorial Orthodoxies" (23 July 1976) [1hr 59.45 mins]

4. Angus Martin, "Specialized Retrospective Checklists: the example of eighteenth-century French Fiction" (8 Oct 1976) [1hr 38.05 mins]

5. Wallace Kirsop, "Bibliographical Detection" (14 October 1977) [1hr 03.07 mins]

* * * * *

From the above it appears that much of the energy of Harold and Wal went into establishing the BSANZ in the early 70s, and that it was only after they had been joined by Brian and others at Monash that the idea of a research Centre at Monash was seriously contemplated.

I am told that in the very early 1980s the Fraser Government proposed establishing ten research centres across Australia. A proposal was hastily assembled by Harold and Brian (Wal was in Cambridge at the time) for a Centre for Bibliographical and Textual Studies at Monash to undertake research for the Early Imprint Project** and to prepare scholarly editions. The Centre was unsuccessful in its bid, but redirected its proposal to the University (sans the request for money), and it was accepted.

Wal and Brian had been responsible for editing all issues of the BSANZ Bulletin from 1970 until this time. Shortly after the Centre was established (in 1982) the editorship was passed on to Trevor Mills (in 1983), allowing Brian and others at Monash to concentrate on Centre activities—including the development of an the interdisciplinary MA in Bibliographical and Textual Studies (restructured in 1994, but was still available in 2001).

Although, I am told, there were few graduates of the Monash "Master of Arts, Centre for Bibliographical and Textual Studies", I have been able to identify four students who produced important work between 1989 and 1999:

1. Linley Horrocks, "The creation of the Anzac market 1914-1918: the role of the press and the book trade" (MA thesis, 1989).

2. John Arnold, "The Fanfrolico Press: history and bibliography" (MA thesis, 1994). ¶ John's Fanfrolico Press: Satyrs, Fauns & Fine Books (Private Libraries Association, 2009) was reviewed by Nathan Garvey in Script & Print 36.2 (2012).

3. Laurel J. Clark, "Aspects of Melbourne book trade history: innovation and specialisation in the careers of F.F. Bailliere and Margareta Webber" (MA thesis, 1997).

4. Peter Pereyra, "Crime-fiction: from publisher to reader" (MA thesis, 1999).

Some significant work—both published and in theses—has also come out of both the "Bibliography and Textual Scholarship" unit and the "Analytical and Descriptive Bibliography" unit, which was offered by the Centre as an elective to M.A., M.Lib. and a few other candidates. This includes:

1. Annemie Gilbert and Sylvia Ransom, "The Imposition of Eighteenmos in Sixes, With Special Reference to Tranchefiles" BSANZ Bulletin 4:4 (1980), 269–75.

2. Penny McCristal, " '$½’ as a statement of signing" BSANZ Bulletin 19:3 (1995), 209–12.

* * * * *

By the time that the Centre was reconstituted in 2010 the principle academics involved in its earlier history had all retired and it was no longer possible for the remaining (emeritus) staff associated with the Centre to teach or take on higher-degree student supervisions. In the eyes of the university, this was a serious problem.

Of course, the Centre remained active in its research and publishing programme, in an academic seminar series, and in obtaining grant funding. And Wal and Brian took an active role in mentoring scholars like myself. (Without the assistance of Wal, Brian and others associated with the Centre, I would never have been able to take on the editorship of Script and Print and get it back up to date in such a short period.)

But, when all ECPS research units were reconstituted in 2010 as research-only units, the Centre needed a director with an outstanding research record who could supervise MA and PhD students. This was Simone.

Interestingly, teaching was specifically excluded from the purview of the new research units, although mentoring—and building the number of—M.A. and Ph.D. students were each among the KPIs. But with the recent university-wide move to force a coursework component on all MA and PhD students—it may be that research units will have some involvement with teaching in future. If so, there is a slight chance that some sort of Centre for the Book unit will be available to MA and PhD students again.

(A brief explanation: All research units and all new MA and PhD students will be administered within a program which is aligned with Field of Research codes (such as 2005–Literary Studies), by a program-manager, and will be supervised by Monash Institute of Graduate Research-approved, research-active staff, affiliated with that program. It seems likely that MA and PhD students will be offered coursework units that are aligned—at least to a certain extent—with the focus of research units within each program. If so, it seems likely that staff in the research units within each program will be called on to do the coursework teaching, as well as the supervision.)

Whether or not research units return to coursework teaching, the Centre for the Book at Monash has a small group of talented PhD students associated with it already and a steady stream of enquiries from would-be students suggests that this group will continue to grow.

**The aim of the Early Imprint Project (subsequently the Australian Book Heritage Resources Project) was to compile a short-title catalogue "in machine readable form" of all books published before 1801 held in Australasian libraries. See B. J. McMullin, "The Australia and New Zealand Early Imprints Project: The Background" BSANZ Bulletin 6:4 (1982), 163–73.

* * * * *

Bryan Coleborne, Chairman of the Committee for the Centre from 1994–96, records some of his thoughts about both the centre and the future of teaching bibliography and book history in his "Course Design and Analytical Bibliography" BSANZ Bulletin 20:3 (1996), 213–17.

Brian McMullin records some of his thoughts in "Bibliography in the Library School at Monash" BSANZ Bulletin 20:3 (1996), 218–20; "Forty Years On" Script and Print 35:2 (2011): 106–7.

Saturday, 12 May 2012

The Prodigal Daughter; Or, Anna Taylor's Warning

The Prodigal Daughter; Or, A Strange and Wonderful Relation (or, indeed, The Disobedient Lady Reclaimed) is an eighteenth-century chapbook story about a "proud and disobedient daughter" who, at the instigation of the devil, attempts to poison her parents.

None of the early editions of this 248-line poem are dated, and the date-ranges suggested for the seventeen editions on ESTC are fairy wide, but a copy held by the American Antiquarian Society appears to be the earliest. It can be dated to "between 1742 and 1754" by the woodcut ornaments that appear before and after the text.

It is not possible to establish an exact sequence for the following sixteen editions on ESTC, but my copy—the 1799 edition printed in Hartford—is the last listed. Three copies of this edition are listed on ESTC, which is more than almost every other edition of the story. So, definitely a rare book.

When I went looking online for information about this story I pretty-much drew a blank. No copies of the text, no discussion of the story, and only a few brief mentions (and a few short quotes) appear in any of the books scanned by Google. I thought this was pretty odd, given the nature of the story, which I will summarise here:

The "fair" daughter of a Bristol merchant—guilty of disobedience, "Swearing and whoring, sabbath breaking too"—responds to her father's attempt to humble her pride by vowing to sell her soul for the money he has threatened to withhold. When he "strip[s] her of her rich array," said daughter calls upon the devil who advises her to poison her parents, which she promptly does.

But, the parents are tipped off by a meddling angel, and so they feed the poisoned meal to their dog! What the dog did to deserve to be knowingly-poisoned in this way, and what punishment the parents face for murdering their innocent dog, is not explained.

The daughter is confronted with her crime, swoons, and as the title-page says "lay in a trance four days; and when she was put into the grave, she came to life again, and related the wonderful things she saw in the other world." (That is, how she was denied entrance into Heaven, argued with the gate-keeper, is shown "the burning lake of misery", repents etc.)

The story is predicable, but fun. You have to wonder whether the story was bought and read by adults and children alike for its no-nonsense heroine and supernatural silliness (i.e, for fun), or if it was only bought by dour parents, who forced their children to read the tale in the vain hope that said long-suffering children would repent from [insert insignificant moral infraction] before trying their hand at poisoning.

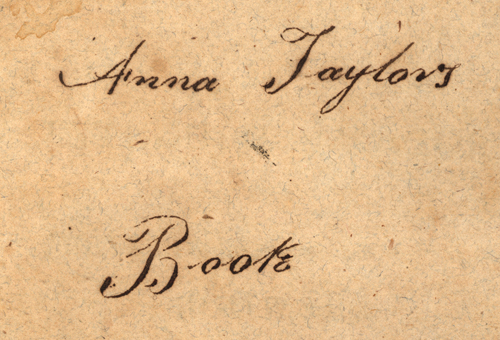

Interestingly, this copy is inscribed "Anna Taylor's Book" in a contemporary hand. So perhaps, this didactic tale was Anna Taylor's warning from her parents: give up your disobedience, sabbath breaking, swearing and whoring(!), before you are dragged off to hell.

And, on that happy thought, here is the text of the 1799 edition [ESTC: w26926; Evans, 36166].

* * * * *

The Prodigal Daughter; Or, A Strange and Wonderful Relation. Shewing, how a Gentleman of great estate in Bristol, had a proud and disobedient daughter, who, because her parents would not support her in all her extravagance, bargained with the devil to poison them. How an angel informed them of her design. How she lay in a trance four days; and when she was put into the grave, she came to life again, and related the wonderful things she saw in the other world (Hartford: Printed for the Travelling Booksellers, 1799).

The Prodigal Daughter; Or, The Disobedient Lady Reclaimed.

LET every wicked graceless child attend,

And listen to these lines that here are penn'd;

God grant it may to all a warning be,

To love their parents and shun bad company.

No further off than Bristol, now of late,

A gentleman lived of a vast estate,

And he had but one only daughter fair,

Whom he most tenderly did love so dear.

They kept her clothed in costly rich array,

And as the child grew up, for truth they say,

Her heart with pride was lifted up so high,

She fix'd her whole delight in vanity.

Each sinful course did to her pleasant seem,

And of the holy scriptures made a game,

At length her patents did begin to see,

Their tender kindness would her ruin be.

Her mother thus to her began to speak,

My child, the course you run my heart will break,

The tender love which we to you have shown,

I fear will cause our tender hearts to groan.

Come, come, my child, this course in time refrain,

And serve the LORD now in your youthful prime,

For if in this your wicked course you run,

Your soul and body both will be undone.

Laughing and scoffing at her mother, she

Said, Pray now trouble not yourself with me,

Why do you talk to me of heaven's joy?

My youthful pleasures all for to destroy?

I am not certain what I shall possess,

After that I've resign'd my vital breath,

I nothing for another world do care,

Therefore I'll take my pleasure while I'm here.

The mother said, my child, how do you know

How soon your pride into the dust may go?

For young as well as old to death bow down,

And you must die God only knows how soon.

She from her mother in a passion went,

Filling her aged heart with discontent;

She wrung her hands and to her husband said,

She's ruin'd, soul and body, I'm afraid.

Her father said, her pride I will pull down,

Money to spend no more, I'll give her none,

I'll make her humble before I have done,

Or else forever I will her disown.

All night she from her father's house did stray,

Next morning she came home by break of day,

Her father he did ask her where she'd been?

She straightway answer'd What was that to him.

He said your haughty pride I will pull down,

Money to spend of me you shall have none,

She said, if you deny me what I crave,

I'll fell my foul, for money I will have.

Her father stripped her of her rich array,

And then he drest her in a russet grey,

And to her chamber he did her confine,

With bread and water fed her for some time.

Altho' their hearts did ache for her full sore,

This course they took her soul for to restore,

But all in vain, she wanted heaven's grace,

And sin within her heart had taken place.

One night as in her room she musing were,

The devil in her room did then appear,

In shape and person like a gentleman,

And seemingly he took her by the hand.

He said, fair creature, why do you lament?

Why is your heart thus fill'd with discontent?

She said, my parents cruel are to me,

And keep me here to starve in misery.

The devil said, if you'll be rul'd by me,

Reveng'd on them you certainly shall be.

Seem to be humble, tell them you repent,

And soon you'll find their hearts for to relent.

And when your father he doth use you kind,

An opportunity you soon will find,

Poison your father and your mother too,

There's none will know who 'twas the fact did do.

This wicked wretch quite void of grace and shame,

Seemed to be well pleased at the same,

She said, your counsel I'm resolv'd to take,

And be reveng'd for what they've done of late.

Where do you live? pray tell me where to come,

That I may tell you when the job is done.

He said, my name is Satan, and I dwell

In the dark regions of the burning hell.

At first she seem'd to be something surpriz'd,

But want of grace so blinded had her eyes,

She said, well sir, if you the devil be,

I'll take the counsel which you gave to me.

But mind what wonders God does every hour,

His mercies are above the devil's power,

He will his servants keep both night and day,

From the devouring subtle serpent's prey.

Next day, when she her father's face did see,

She instantly did fall upon her knee,

Saying; father now my wicked heart relents,

And for my sins I heartily repent.

Her father then with tears did her embrace,

Saying, I'm blest for this small spark of grace,

That heaven hath my, child bestow'd on thee;

No more I'll use you with such cruelty.

Unto her mother then straightway he goes,

And told to her the blest and happy news.

Her mother was rejoic'd then for her part,

Not knowing of the mischief in her heart.

But the Almighty her designs did know,

And 'twas his blessed will it should be so,

That other graceless children they might see,

All things are done by heaven's great decree.

The poison strong she privately had bought,

And only then the fatal time she sought,

To work the fall of these her parents dear,

Who'd brought her up with tender love and care,

One night her parents sleeping were in bed,

Nothing but troubled dreams run in their head;

At length an angel did to them appear,

Saying, awake, and unto me give ear.

A messenger I'm sent by heaven kind,

To let you know your deaths are both design'd,

Your graceless child whom you do love so dear,

She for your precious lives hath laid a snare.

To poison you, the devil tempts her so,

She hath no power from the snare to go;

But God such care doth of his servants take,

Those that believe on him he'll not forsake.

You must not use her cruel and severe,

For tho' to you these things I do declare,

It is to shew you what the Lord can do,

He soon can turn her heart, you'll find it so.

Pray to the Lord his grace for to send down,

And like the prodigal she will return;

The fatted calf with joy you'll kill that day,

The angels shall rejoice in heaven high,

Because a wretched sinner doth repent,

Who in vice and sin her time hath spent.

This pious couple then awoke we hear,

And soon the angel he did disappear.

They to each other did the vision tell,

And from this time we'll mark her actions well,

And if this vision unto pass does come,

We'll praise the Lord for such great favors done.

Next morning she rose early, as we hear,

And for her parents' breakfast did prepare,

And in the fame she put the poison strong,

And brought it unto them when she had done.

Her father took the victuals which she bro't,

And down the same unto the dog he set,

Who ate the food and instantly did die;

The case was plain, she could not it deny.

They call'd her there the sight for to behold,

Which when she saw, her spirits soon ran cold,

She cry'd, the devil hath me now deceiv'd,

I've miss'd my aim, for which I'm sorely griev'd.

Her mother said, hard is the fate of me,

I've been a tender mother unto thee,

And can you seek to take my life away?

Oh graceless child! what will become of thee?

With bitter pains my child, I did you bear,

I taught you how the Lord of life to fear,

Whole days and nights I did in labor spend,

To bring you up, now to my discontent.

Quite void of grace you in your sins do run,

You flight my counsel after all I've done,

Instead of obedience which you ought to pay,

Your parents' lives you seek to take away.

When thus she heard her tender mother speak,

She in a swoon did drop down at her feet,

With all the arts that e'er they could contrive,

They could not bring her spirit to revive.

Four days they kept her, when they did prepare,

To lay her body in the dust we hear,

At her funeral a sermon then was preach'd,

All other wicked children for to teach,

How they should fear their tender parents kind,

Their words observe their counsel for to mind,

And then their days will long be in this land,

All things will prosper which they take in hand.

So close the Reverend Divine did lay

This charge, that many wept that there did stay

To hear the sermon, and her parents dear

Were overwhelm'd with sorrow, grief and care.

The sermon being over and quite done,

To lay her body in the dust they come,

But suddenly they bitter groans did hear,

Which much surprized all that then were there.

At length they did perceive the dismal sound

Come from the body just laid under ground;

The coffin then they did draw up again,

And in a fright they opened the same,

When soon they found that she was yet alive,

Her mother seeing that the did survive,

Did praise the Lord, in hopes she would have time

And would repent of all her heinous crimes.

She in her coffin then was carried home,

And when unto her father's house she come,

She in her coffin sat and did admire

Her winding sheet, and thus she did desire

The worthy minister for to sit down,

And she would tell the wonders which were shown

Unto her, since her soul had took its flight:

She'd seen the regions of eternal night.

She said, when first my soul did hence depart,

For to relate the story grieves my heart,

I handed was to lonesome wild desarts,

And briery woods, which dismal were and dark.

The briars tore my flesh, the gore did run,

I call'd for mercy but I could find none;

But I at length a glimpse of light did spy,

And heard a voice which unto me did cry,

Now sinful soul observe and you shall see

How precious does that light appear to thee?

But in the regions of eternal night

You never must expect for to see light.

Now hasten to that light which does appear,

And there your sentence you shall quickly hear.

I hearing this did hasten then along,

At length unto a spacious gate I come.

I knock'd aloud, but no one answer made;

At length one did appear to me and said,

"What want you here?" I answered to come in,

He ask'd my name then shut the gate again.

He staid awhile then to the door did come,

He said be gone, for you there is no room,

For we have no such graceless wretches here,

That disobey their tender parents dear.

I sorely wept, and to the man thus said,

Am I the first that parents disobey'd?

If all be cast in hell who thus do sin,

Few at this gate I fear will enter in.

He said but you have been a sinner wild,

In things besides a disobedient child,

Swearing and whoring, sabbath breaking too,

Therefore be gone, for here's no rest for you.

I said, Sir, hear me, and remember pray,

How holy David he did run astray,

A man whose heart once with the Lord did join,

Adultery and murder was his crime.

He said, like David you did not return,

For he in ashes for his sins did mourn,

And God is merciful you well do know,

Free to forgive all those that humble so.

I still my case with him pursu'd to plead,

And told him, Sir, in scripture I did read,

How Mary Magdalen, who here doth rest,

At once by many devils was possest.

Go silly woman, he did answer then,

Had you so much lamented for your sin,

And mercy at your Saviour's feet implor'd,

For all your fins, he had your soul restor'd.

I said in prison she her Saviour saw:

He said, you may behold him every day,

He ne'er leaves those that in his mercy trust,

He's always with the pious and the just.

In holy scripture there he doth appear,

Read the apostles, and you'll find him there;

You mull believe, if that you sav'd will be,

That Christ for sinners died upon a tree.

Then save me Lord, I to him did reply,

For I believe that Christ for me did die;

Lord let my soul return from whence it came,

And I will honour thy most holy name.

A voice I heard, which said to me return,

But first behold the wretched place of doom,

Where the reward of sin is justly paid.

I turn'd about, but sadly was dismay'd.

I saw the burning lake of misery,

I saw the man there that first tempted me,

My loving tender parents for to slay,

And he both fierce and grim did look at me.

He told me he at last was sure of me.

I said, my Saviour's blood has set me free.

Then in a hideous manner he did roar,

When God my senses did to me restore.

When thus the story she to them had told,

She said, put me to bed for I am cold,

And then these my tender parents dear,

Whom I will always honour while I'm here.

To them the sacrament she did require,

They gave it her then as she did desire,

And now she is a Christian just and true,

No more her wicked vices doth pursue.

I hope this will a good example be,

Children your parents honour and obey,

And then the Lord will bless you here on earth,

And give you crowns of glory after death.

FINIS.

[UPDATE: 2 July 2016: After all my pictures disappeared from this site (again) I decided to give up on external hosts for large versions (1000px) of my image files and, for now on, will stick with the smaller images (500px), which Blogger is prepared to host.]

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)